Kingdom of Dalmatia

Medieval Dalmatia included only some particular cities and isles who were under really or nominally Byzantine rule. Although Dalmatia had a title of the kingdom (regnum), during the Middle Ages it never existed as an united entity. The cities (Dubrovnik, Zadar, Split, Kotor, Trogir) were closed communes and all of them would independently decide their own fate.

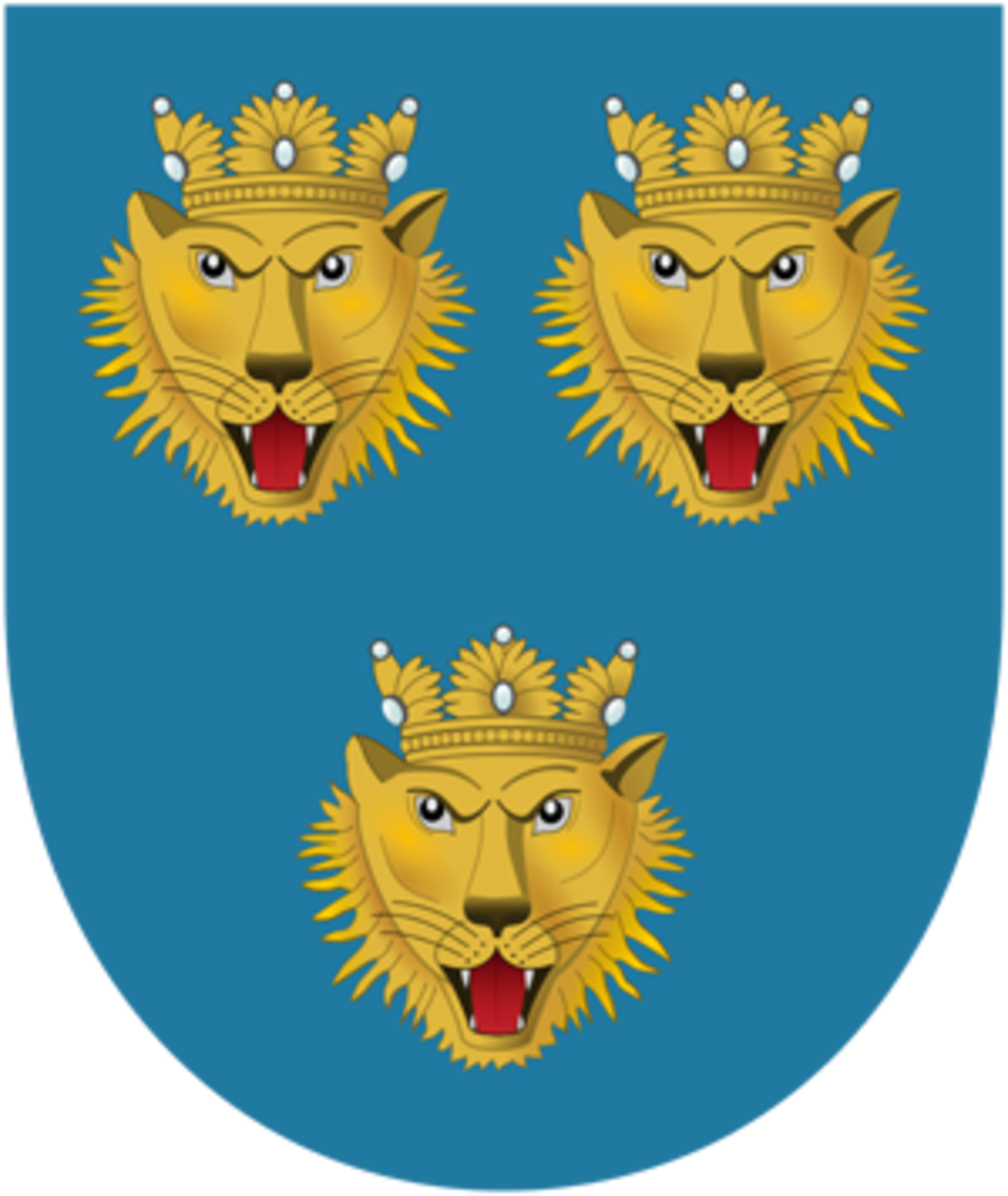

Coat of arms

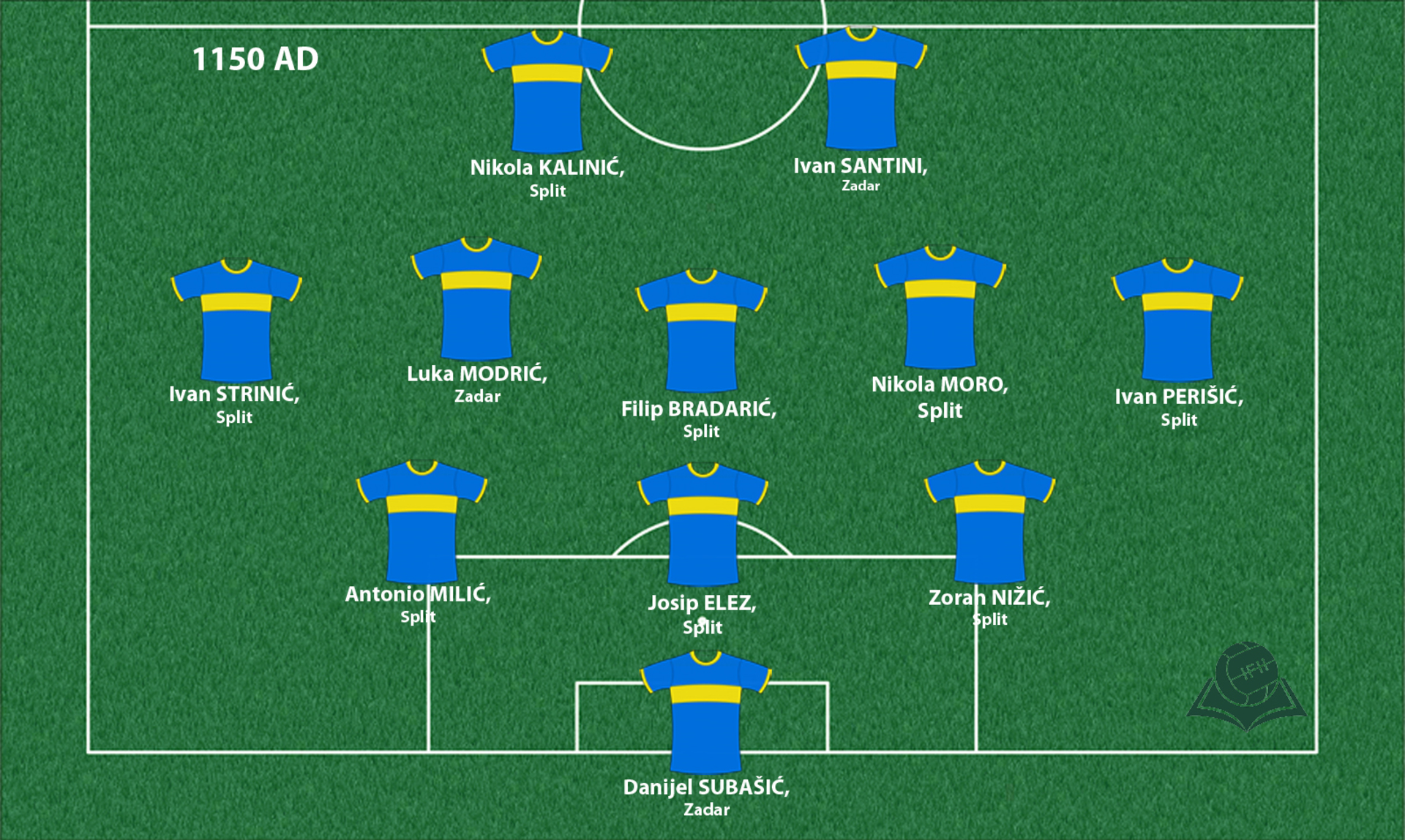

Shirt

| Position | First name | Last name | Mjesto rođenja | Like | Dislike | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GK | Danijel | SUBAŠIĆ | Zadar |

70 |

5 |

|

| GK | Dominik | LIVAKOVIĆ | Zadar |

15 |

2 |

|

| GK | Lovre | KALINIĆ | Split |

37 |

5 |

|

| DC | Emir | SPAHIĆ | Dubrovnik |

13 |

4 |

|

| DC | Goran | MILOVIĆ | Split |

9 |

5 |

|

| DC | Josip | ELEZ | Split |

12 |

3 |

|

| DC | Lorenco | ŠIMIĆ | Split |

10 |

0 |

|

| DC | Petar | BOSANČIĆ | Split |

8 |

2 |

|

| DC | Zoran | NIŽIĆ | Split |

14 |

4 |

|

| DLC | Antonio | MILIĆ | Split |

14 |

1 |

|

| DL | Ante | VRLJIČAK | Split |

3 |

6 |

|

| DL | Ivan | STRINIĆ | Split |

30 |

6 |

|

| DMC | Andrija | BALIĆ | Split |

12 |

0 |

|

| DMC | Josip | RADOŠEVIĆ | Split |

11 |

1 |

|

| MC | Luka | MODRIĆ | Zadar |

90 |

8 |

|

| MC | Marko | BAKIĆ | Budva |

3 |

4 |

|

| MC | Nikola | MORO | Split |

11 |

3 |

|

| AMC | Franko | ANDRIJAŠEVIĆ | Split |

11 |

2 |

|

| AMC | Mijo | CAKTAŠ | Split |

10 |

2 |

|

| AMRL | Alen | HALILOVIĆ | Dubrovnik |

17 |

12 |

|

| AMRL | Ivan | PERIŠIĆ | Split |

80 |

5 |

|

| AMRL | Marin | TOMASOV | Zadar |

7 |

4 |

|

| AMRL | Nikola | VLAŠIĆ | Split |

41 |

3 |

|

| AMRL/FC | Ante | ERCEG | Split |

12 |

1 |

|

| AMRL/FC | Staniša | MANDIĆ | Herceg Novi |

6 |

5 |

|

| FRLC | Ante | REBIĆ | Split |

41 |

1 |

|

| FRLC | Marko | LIVAJA | Split |

12 |

1 |

|

| FC | Ivan | SANTINI | Zadar |

22 |

5 |

|

| FC | Nikola | KALINIĆ | Split |

48 |

11 |

|

| FC | Stipe | PERICA | Zadar |

14 |

2 |

(Today part of: coastal part of region Dalmatia in Croatia, coastal Montenegro)

The term “Dalmatia” has changed throughout the centuries. While the Roman province of Dalmatia had reached all the way to the river Drina, Avars and Slavic invaders during the 6th and 7th century had reduced Dalmatia to eastern-Adriatic cities, from Kvarner in the north to Kotor in the south. Although, not the entire coast. Some of the less developed towns (Biograd, Šibenik) were in the Kingdom of Croatia, which was situated in Dalamtia continental hinterland. Of course, medieval borders were not strictly defined as today. For example, by the time, Šibenik became increasingly similar to the Dalmatian cities, and at the end of the 13th and early 14th century, it strengthened its status as an autonomous commune, and occasionally recognized the authority of Venice.

Seen as how Byzantium’s hold over them was only symbolic, since the 10th century it had named the rulers of the Kingdom of Croatia. At the end of the 10th and the beginning od the 11th century, some of them had even added the title of the King of Dalmatia to their other titles, which, at least in theory, meant the unification of these two political entity under the unique Kingdom. At the same time, these cities would, at times, acknowledged the rule of Venice, which had governed them in the Emperor’s name and with his permission. Doge of Venice had also put a name of Dalmatia in his title.

Organized in the style of communes they had resisted all attempts against their self-sufficiency. The communes were subordinated only to central power, which will, in the 12th century, find itself in the hands of Venetian doges, (Croatian-)Hungarian kings, and sometimes local Croatian and Bosnian noble families. Additionally, Byzantium will also claim its historical right to themfrom all the way back in the 5th century. The population was never divided according to a lingual (Slavic, Romanesque) or ethnic line, they would rather differentiate between themselves as “Split folk” and “non-Split folk,” or “Zadar folk” and “non-Zadar folk.” Independent of one another, Dalmatian cities had their own patron saint and strong local patriotic spirit. Nevertheless, in 1409 AD, the doge had bought the rights to Dalmatia from the defeated pretender for the Hungarian throne, so they will stay under the rule of the Venetian Republic until the end of the 18th century. Dubrovnik was the only exception, and it will grow into an independent state with an aristocratic-republican system of government (Repubblica di Ragusa).

Sources

- Neven BUDAK, Tomislav RAUKAR, Hrvatska povijest srednjeg vijeka, Zagreb, 2006.

- Vinko FORETIĆ, Studije i rasprave iz hrvatske povijesti, Split, 2001.

- Emil HERŠAK, »Hrvati od gusarske drŽave do samostalnosti", poglavlje u knjizi: Carlo Alberto Brioschi, Kratka povijest korupcije. Zagreb 2007.

- Marko PIJOVIĆ, ''Pristupi proučavanju identiteta u prošlosti'', Historijska traganja, 8/2011., 9-60

- Ivo RENDIĆ MIOČEVIĆ, Zlo velike jetre, Split, 1996.

- ''U potrazi za mirom i blagostanjem: hrvatske zemlje u 18. Stoljeću'', Povijest Hrvata, sv. V, (ur.Lovorka Čoralić), Zagreb, 2013.

- Ivo Glavaš, ''Koliko znamo o najranijoj povijesti Šibenika'', http://m.sibenik.in/zaboravljeni-sibenik/koliko-znamo-o-najranijoj-povijesti-sibenika/51032.html

- ''Komuna'', http://www.enciklopedija.hr/Natuknica.aspx?ID=32683

- Coat of arms: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coat_of_arms_of_Dalmatia